“People will think what I want them to think!” – Charles Foster Kane (Orson Welles)

Citizen Kane is the greatest film of all time according to many people, including the American Film Institute, Sight & Sound magazine, and film critic Roger Ebert. It seems Kane’s commandment for people to think what he wants them to think has taken on the resonance of self-fulfilling prophecy.

With a film so thoroughly parsed and analyzed, you can’t really review Citizen Kane—you just have to experience it. And the TCM Classic Film Festival provided one hell of an experience. Screening a newly restored digital print at the enormous, gorgeous picture palace of Grauman’s Chinese theater, Citizen Kane was a mighty spectacle. Perhaps you have not seen the film and scoff at the hype surrounding its status as Greatest Film of All-Time. Oh, no, my friend. Believe the hype. Although such designations are arbitrary, Kane is an almost indefensibly solid choice for the #1 spot. Celebrating its seventieth anniversary this year, Welles’ masterpiece is as modern as the day it debuted and, impossible though it may seem, somehow still comes across as fresh, innovative and something heretofore unseen in cinema.

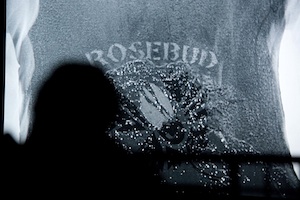

Welles plays Charles Foster Kane, world famous newspaper tycoon and all-around sonuvabitch. The film opens with Kane’s death, and then thrusts us into an overview of his life’s accomplishments with a brilliant montage of faux-newsreel footage. The movie then turns into a sort of detective story, as a young reporter named Thompson interviews the people in Kane’s life who give little glimpses into the complex and inscrutable titan.

Interestingly, Thompson’s face is never shown to the audience. He comes to represent the flip side of Kane’s ubiquitous megalomania. Whereas Charles Foster Kane was a world-famous celebrity, recognized by all and known to few (if any), Thompson is the new “face” of journalism: the anonymous, nose-to-the-grindstone reporter whose personal glorification is never privileged above the story he reports. Thompson’s introduction is one of the most famous shots in the film (and all of cinema history): a group of reporters are backlit in a dark, smoky screening room having just finished watching a “News on the March” newsreel recapping Kane’s life and death. Smash cut from the newsreel to the smoky room, an immediate transition between the film within a film and our new detective narrative.

Interestingly, Thompson’s face is never shown to the audience. He comes to represent the flip side of Kane’s ubiquitous megalomania. Whereas Charles Foster Kane was a world-famous celebrity, recognized by all and known to few (if any), Thompson is the new “face” of journalism: the anonymous, nose-to-the-grindstone reporter whose personal glorification is never privileged above the story he reports. Thompson’s introduction is one of the most famous shots in the film (and all of cinema history): a group of reporters are backlit in a dark, smoky screening room having just finished watching a “News on the March” newsreel recapping Kane’s life and death. Smash cut from the newsreel to the smoky room, an immediate transition between the film within a film and our new detective narrative.

The image is, simply put, breathtaking. And I do mean that literally. Welles and cinematographer Gregg Toland’s groundbreaking work on Citizen Kane is the stuff of legend, but this particular shot—the way it plunges you headlong into the murky, deep focus world of the reporters literally in the dark—actually stopped my breathing.

The screening was introduced by TCM weekend daytime host Ben Mankiewicz, an appropriate choice considering it was Mankiewicz’s own grandfather Herman Mankiewicz who wrote the screenplay for Citizen Kane—and earned the film its single Academy Award. The younger Mankiewicz recalled his grandfather’s triumph over the film, as well as some rough patches. Charles Foster Kane, as most people know, was a very thinly veiled caricature of newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, pioneer of “yellow journalism” and who, in the first half of the last century, had a virtual monopoly on the American press. As such, Hearst resented the film and Hearst-controlled papers were among the only publications to give Kane poor reviews.

Herman Mankiewicz, as the chief architect of the film (with co-writer Welles), felt Hearst’s wrath first-hand. One night, Herman was involved in a minor car accident in the Hollywood Hills. No one was hurt, and in fact the other driver was the wife of an acquaintance; no harm done. No harm, that is, until Hearst reporters got a hold of the story and splashed it across the front page of their papers for weeks.

Joining Ben Mankiewicz for a lively discussion was Norman Lloyd, the 96-year old film and theater actor who worked with Orson Welles at the Mercury Theater in New York. Under Welles’ direction, the Mercury Theater became the stuff of legend, staging groundbreaking productions of Shakespeare and notorious radio broadcasts like 1938’s panic-inducing The War of the Worlds. Founded by Welles and producer John Houseman, the Mercury Theater was the most dynamic group of artists in the country and the screen debut of the company was hotly anticipated. Lloyd’s first major role in a Mercury production was 1937’s Julius Caesar. The new staging was a modern re-appropriation of Shakespeare’s historical work that commented on (then) modern-day fascism. It was a sensation. Twenty-five years later, Houseman produced a film adaptation starring Marlon Brando that earned five Academy Award nominations (including Best Picture for Houseman) and one win. Incensed, Welles accosted John Houseman one night in a restaurant and threw a Sterno can at Houseman’s head, screaming: “You stole my play!” Never one for modesty, Welles truly believed, perhaps justifiably, that Julius Caesar no longer belonged to William Shakespeare.

Joining Ben Mankiewicz for a lively discussion was Norman Lloyd, the 96-year old film and theater actor who worked with Orson Welles at the Mercury Theater in New York. Under Welles’ direction, the Mercury Theater became the stuff of legend, staging groundbreaking productions of Shakespeare and notorious radio broadcasts like 1938’s panic-inducing The War of the Worlds. Founded by Welles and producer John Houseman, the Mercury Theater was the most dynamic group of artists in the country and the screen debut of the company was hotly anticipated. Lloyd’s first major role in a Mercury production was 1937’s Julius Caesar. The new staging was a modern re-appropriation of Shakespeare’s historical work that commented on (then) modern-day fascism. It was a sensation. Twenty-five years later, Houseman produced a film adaptation starring Marlon Brando that earned five Academy Award nominations (including Best Picture for Houseman) and one win. Incensed, Welles accosted John Houseman one night in a restaurant and threw a Sterno can at Houseman’s head, screaming: “You stole my play!” Never one for modesty, Welles truly believed, perhaps justifiably, that Julius Caesar no longer belonged to William Shakespeare.

Lloyd also recalled the perculiariities of Kane composer Bernard Herrmann, who he affectionately termed a “difficult eccentric,” and an “irascible Anglophile with a bit of a belly.” Although he had worked with Welles at the Mercury Theater, Citizen Kane was Herrmann’s first film score. Incredibly, he earned an Academy Award nomination his first time out, but lost to himself for All That Money Can Buy the same year. Herrmann went on to perhaps the most remarkable career by any composer in film history, getting his start with Orson Welles, followed by a fruitful and memorable collaboration with Alfred Hitchcock, and capping it all off by scoring Taxi Driver for Martin Scorsese—earning one Oscar and five nominations.

Although not chosen from the Mercury theater group to star in Citizen Kane, Norman Lloyd made his no-less auspicious debut a year later in Alfred Hitchcock’s Saboteur. There are not many people who have had firsthand working knowledge of both Orson Welles and Alfred Hitchcock, so naturally the audience was eager to hear Lloyd’s opinion on the two cinema masters. Although he stressed the futility of comparing two directors who are so different in their approaches to film, Lloyd nevertheless indulged everyone’s curiosity. He compared Hitchcock’s use of “camera logic” to Welles’ Gothic “theatricality.” Hitch, he said, knew instinctively where the camera should be at any given time to convey the elements of the story. Welles, in contrast, was not as skilled as a storyteller because he was more interested in staging the action to exaggerate its baroque and nightmarish angles. Welles’ interest in theatrical excess is readily apparent in the direction of Citizen Kane whose visuals are alternately cramped and dynamic, stately and stylized.

Although not chosen from the Mercury theater group to star in Citizen Kane, Norman Lloyd made his no-less auspicious debut a year later in Alfred Hitchcock’s Saboteur. There are not many people who have had firsthand working knowledge of both Orson Welles and Alfred Hitchcock, so naturally the audience was eager to hear Lloyd’s opinion on the two cinema masters. Although he stressed the futility of comparing two directors who are so different in their approaches to film, Lloyd nevertheless indulged everyone’s curiosity. He compared Hitchcock’s use of “camera logic” to Welles’ Gothic “theatricality.” Hitch, he said, knew instinctively where the camera should be at any given time to convey the elements of the story. Welles, in contrast, was not as skilled as a storyteller because he was more interested in staging the action to exaggerate its baroque and nightmarish angles. Welles’ interest in theatrical excess is readily apparent in the direction of Citizen Kane whose visuals are alternately cramped and dynamic, stately and stylized.

![]()