Not to get overly political, but it’s all over the news that the events of the first week of the Trump administration reminded enough Americans of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four to rocket the 1949 book to the top of the bestsellers list again, almost seventy years after it was written. For those who don’t like to read, the prophetic novel has been made into a movie not once, but twice. The first time was in 1956, just a few years after its initial publication. But, the definitive cinematic imagining of the story was the later one, both made in 1984 and entitled 1984.

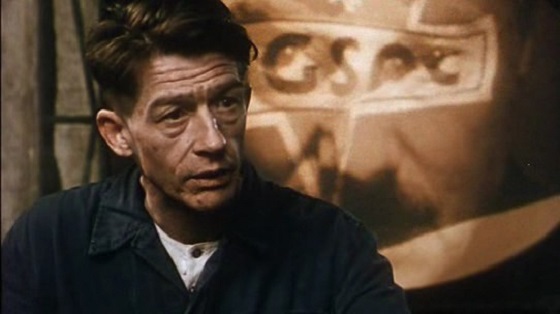

There’s a second, sadder reason why 1984 is the subject of this week’s Cinema Fearité column; its leading man, the great John Hurt, best known for the infamous chest-bursting scene in Alien and for his emotional portrayal of the title character in The Elephant Man, passed away after a two-year battle with pancreatic cancer. Hurt was one of the most celebrated and storied British actors of his time, and worked right up until his death, playing Jacqueline Kennedy’s priest in 2016’s Oscar-bait Natalie Portman vehicle Jackie. With all the quality roles on Hurt’s resume, 1984 may be the most meaningful to today’s world.

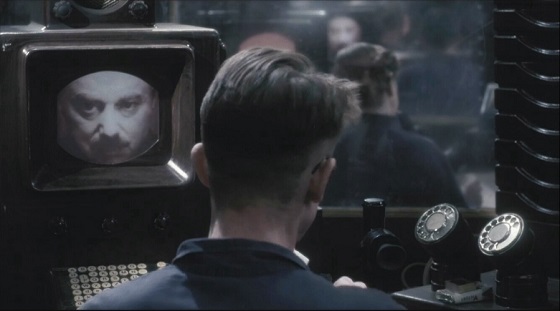

Set in a war-torn futuristic dystopian country called Oceania which emerged in the place of Great Britain, 1984 is about a man named Winston Smith (Hurt) who works for the Ministry of Truth, a misnamed organization that rewrites history to fit the needs of the Party, a governmental agency led by an imposing and enigmatic figure known as Big Brother. When Winston goes home, however, he commits the crime of free thought, writing down his memories and ideas in a secret journal. Winston’s life is changed when he meets a woman named Julia (Brimstone & Treacle’s Suzanna Hamilton) with whom he begins an illicit affair. However, with cameras and microphones everywhere, nothing in Oceania stays secret for long, and Winston and Julia know that it’s only a matter of time before the Thought Police, led by a menacing agent named O’Brien (Richard Burton from Exorcist II: The Heretic), catch them.

It may not be a horror movie in the traditional sense, but the ideas behind 1984 are terrifying. Writer/director Michael Radford (Il Postino: The Postman) adapted Orwell’s novel himself for the screen and chose to shoot the movie during the exact timeframe in which the book took place (late spring of 1984) and in the same location (London). Whenever possible, Radford even shot scenes on the exact dates to which those events corresponded to Winston’s diary entries in the novel. It wasn’t exactly a snapshot of present-day 1984, but Orwell’s vision came to life as one of the most creepily minimalistic science fiction films ever made.

George Orwell was only off by about thirty years or so in many of his predictions. The film opens with a title card which states that “who controls the past controls the future, who controls the present controls the past.” Winston’s job of erasing and changing historical news and events is eerily similar to the current American administration’s concept of “alternative facts.” The constant spying and invasion of privacy that the government exercises on its citizens in the film is reminiscent of the “anti-terrorism” acts which allow the United States National Security Agency to collect phone and computer data from American citizens without their knowledge or consent – and that’s not even mentioning the ever-present security cameras that have popped up on seemingly every street corner in the country. Finally, there’s the never-ending war that the freethinkers understand is not being waged by Oceania against its enemies, but by the oligarchy against the working classes, and it’s a war that is not meant to be won, it’s function is that of a red herring to keep the people docile and afraid to not trust in Big Brother. Does any of this sound familiar?

But enough about politics. Let’s talk about the movie. John Hurt’s performance in 1984 is restrained and vulnerable. Winston is a reluctant hero, and Hurt plays him with a perfect combination of suppressed intelligence and cautious hope. Hurt projects both confidence and fear into his character, so Winston is both likeable and relatable, even in a story that no one wants to believe could actually happen. More importantly, he makes the audience feel the anxiety and oppression that Winston goes through every day. While 1984 is not one of Hurt’s more legendary movies, his performance is extremely effective.

Initially, Michael Radford and cinematographer Roger Deakins (Sicario, Prisoners) wanted to shoot 1984 in black and white. When the production studio balked, a bleach-bypass process was used to tone down and wash out the colors, leaving the film with a distinct look of grimy desolation and hopeless despair. Subsequent reissues of the film have used unbleached master elements, so many versions of 1984 that exist today do not look the way that Radford and Deakins intended them to look, instead bringing the images back to their normal color saturation.

The photography is not the only inconsistency with the different versions of 1984. There are two different musical soundtracks as well. Composer Dominic Muldowney (Bloody Sunday) did the original cinematic score for the film, including the national anthem “Oceania, ‘Tis for Thee.” Producers wanted a chart-topping pop act to supply the music and replaced most of Muldowney’s orchestral score with an electronic one composed by synth-pop band Eurythmics. In the end, both Muldowney and Eurythmics were credited, but most of the theatrical prints included the Eurythmics score, much to Radford’s dismay. Subsequent reissues have had Muldowney’s more traditional film score restored.

It was a bit gimmicky for 1984 to be made and released in 1984, but the movie wasn’t alone in its trendiness; seemingly every high school literature class taught the book that year. One would think with all of the knowledge of the prophetic novel, Orwell’s futuristic vision could have been avoided, yet here we are. Of course, the world today is not exactly how it is in 1984, but some aspects of the book and subsequent movie have come true. And it took longer to get here than Orwell expected, so the rest may not be far behind.