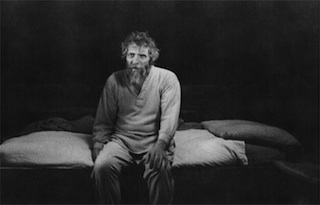

In an alternate universe, a Turin Horse will become the name for a movie that turns out to have nothing to do with its title. Slow-cinema maestro Béla Tarr’s latest (last?) opens with a blank-screen voiceover relating the semi-apocryphal story of Nietzsche’s madness-inducing encounter with a mistreated carthorse, and declares that “of the horse, we know nothing”.  Cut to a carthorse, trudging through a hellish swirl of mist. But this is not necessarily the same horse, we are clearly not in Italy, and the film soon lets the animal retreat to the background, in order to focus exclusively on the slow, hard, regular days of the old carter and his daughter. He has an apostle’s beard and a mop of grey curls, frequently backlight-haloed, and the use of only his left arm; she has a hard, handsome face, tight-mouthed and dead-eyed, beneath long wind-whipped hair; and they live a life of emptiness and hardship in a stone croft on a barren plain.

Cut to a carthorse, trudging through a hellish swirl of mist. But this is not necessarily the same horse, we are clearly not in Italy, and the film soon lets the animal retreat to the background, in order to focus exclusively on the slow, hard, regular days of the old carter and his daughter. He has an apostle’s beard and a mop of grey curls, frequently backlight-haloed, and the use of only his left arm; she has a hard, handsome face, tight-mouthed and dead-eyed, beneath long wind-whipped hair; and they live a life of emptiness and hardship in a stone croft on a barren plain.

Long, slow takes are the order of the day, of course, although Tarr and DP Fred Kelemen rarely hold for long on an empty frame. The camera steadicam glides around the couple’s activities over the course of six similar days, as they eat their unchanging meal of boiled potato and a pinch of salt, or simply gaze out of the window. The technical aspect of the film is truly marvelous, an almost pathological avoidance of the cut by movement and reframing that speaks wonders of the operators’ stamina and agility, and Kelemen’s complex, invisible lighting. With irresistible immediacy, one gorgeous composition follows another, frequently in the same shot, in familiar dirty Tarr blacks and empty whiteness. The camera calms down towards the end, as the pair’s energy diminishes, and winds up in the last section with two stunning images: the first, inexplicably moving, of the daughter staring ghost-like from the window; then finally, of the pair seated at the old oak table in Old Master lighting, abstracted from reality.

All the while, a ghastly wind storm rages outside. Its terrible howling is tears across the soundtrack, but alternated with a simple musical refrain, an AABC violin theme played over and over against scraping strings and organ ostinato like some purgatorial devil’s dirge, repeated forever.  Excitement comes halfway through in the form of a sudden neighbour, who tells them that the wind has blown the town away, that life is now “the most ghastly existence you can imagine” and that the great and noble are nowhere now to be found, having lain down before the acquisitive. The apocalyptic tone is hardly countered by the old man’s “that’s rubbish”.

Excitement comes halfway through in the form of a sudden neighbour, who tells them that the wind has blown the town away, that life is now “the most ghastly existence you can imagine” and that the great and noble are nowhere now to be found, having lain down before the acquisitive. The apocalyptic tone is hardly countered by the old man’s “that’s rubbish”.

The horse swiftly (relative, in the context) gives up moving, and then eating. The well runs dry. They pack their belongings and leave, then inexplicably return, presumably for lack of point. The father stops eating. The lamps mysteriously go out – “what is this darkness?” the daughter asks. She stops eating. Although the horse is clearly not Nietzsche’s, the world of the film is the one he saw in a flash of depressive lucidity, as the legend would have it, a world of pointless, never-ending, self-perpetuating hardship and cruelty. Tarr’s vision of life is certainly nasty and brutish, though not necessarily short, and full of false endings before it finally sputters. We were fortunate enough to have Tarr himself to introduce the screening, and he described the film as ugly, boring, miserable and slow, which is perfectly right. He also says that this will be his farewell to film-making which, with such a hopeless frame of mind, may be just as well.

More information on the film from AFI FEST: The Turin Horse

Read the Q&A with Director Bela Tarr after the screening at AFI FEST: Don’t Call The Turin Horse Bleak

![]()