We’re halfway through the American Cinematheque’s wonderful Fassbinder retrospective, and if it’s demonstrated one thing, it’s that a Fassbinder double bill is a hell of a lot of cinema. His work rate was so prolific that one would assume a film here and there to have been merely tossed off. Some of them were, but his remarkable sense of how drama plays, and what can be done with the camera to enhance that drama, repeatedly finding variations on obsessive themes – the self-perpetuating hierarchy of power and control, in socio-economic or love-relationship terms, and the impossibility of freedom – is so sure that every single one is an immersive viewing experience, rich in text and subtext. It is as though Fassbinder had an innate, instinctive film-making ability, which works even when it shouldn’t: asked by Peter Chatel, his envoy to present Despair (1977) at Cannes, why there’s lots of Nazis at the start but almost none later on, Fassbinder confessed he’d forgotten to film them. Chatel protested that he couldn’t tell that to people; of course not, replied Fassbinder, just tell them that in 1933 the Nazis were a new thing, but that later on people had become insidiously inured to them. It works.

There’s only been one of the later, specifically historical films so far, Fassbinder’s international breakthrough, The Marriage of Maria Braun (1978). It’s success was partly due, the strange ambiguity of the ending aside, to its being one of his most classical, or formally easy-going films (there’s even comparatively few mirrors). This has also allowed people to make all sorts of allegorical claims for it in terms of post-war Germany and the woman’s place in it. The extraordinary soundtrack – frequent pneumatic drills that sound like machine guns; repeated,  and loud, radio broadcasts – lend themselves to this, but it is also another demonstration of how love is colder than death. Rather than being the Mata Hari of the Economic Miracle in terms of class-war, Maria is a Mata Hari of emotional relationships, able to manipulate her way to wealth and success for the sake of her dream of love, even if that love looks suspiciously like a dramatic device (she thrives on his absence).

and loud, radio broadcasts – lend themselves to this, but it is also another demonstration of how love is colder than death. Rather than being the Mata Hari of the Economic Miracle in terms of class-war, Maria is a Mata Hari of emotional relationships, able to manipulate her way to wealth and success for the sake of her dream of love, even if that love looks suspiciously like a dramatic device (she thrives on his absence).

Love is a tricky subject in Fassbinder, something in which he seems frequently not to believe, and which in fact he rarely portrays onscreen. When characters fall in love in his films, it is usually perfunctory. Maria’s is born of three weeks of courtship, and two days and a night of marriage; in Fox and his Friends (1974), The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1972), and countless others, the couples fall in love just like that. Almost always, the love is one-sided from the start. Love for Fassbinder is being in thrall to someone else, a masochistic devotion; or, for the other party, a successful need to dominate. And it never ends well.

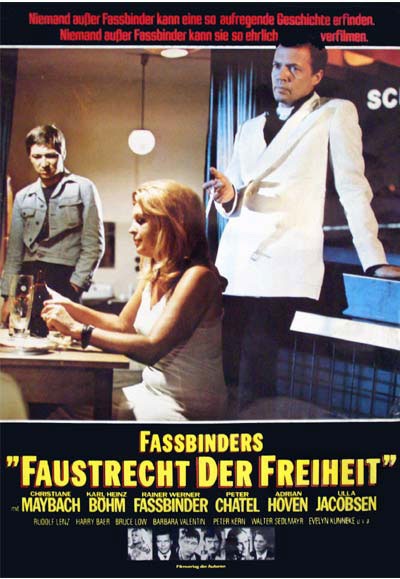

Fox and his Friends was criticized on its release for being relentlessly negative in this fashion, as the lottery-winning carny is methodically fleeced by his posh boyfriend. The story develops with characteristic rigor, however, and is a focused expression of personal beliefs; not least since Fassbinder takes the role, as his dedication puts it, of Armin and all the others, dominated, exploited, and destroyed, as would be many of his own partners (his lover Armin Meier resorted suicide). It was criticized also for its depiction of homosexuality – they repeatedly give each other feminine pet names, are generally prissy, and are really not very nice people; but then nor are the straights in the other films, and it undeniably fulfils Fassbinder’s aim to make a gay film where gayness is not the issue.

Petra von Kant plays like a reverse of this, with the upper-middle class Petra laid low by her love for a working class model, who uses Petra to advance herself.  Again, didn’t go down well with women and gays, but neither is the point – it’s just more of people trampling on other people, explicitly harking after All About Eve. Stunning on the big screen, it’s full of formal tensions, from the deliciously polite battle between two stars, Carstensen and Schygulla, to the incredible camera moves and blocking within an undisguised theatrical set-up (5 acts, one set). Carstensen is fantastic, and puts the lie to Petra’s own claim that everyone is replaceable, even if the mannequins in her studio mimic the actress’s postures. The only man in the film is a tiny little penis on the awesome Poussin reproduction that covers one wall.

Again, didn’t go down well with women and gays, but neither is the point – it’s just more of people trampling on other people, explicitly harking after All About Eve. Stunning on the big screen, it’s full of formal tensions, from the deliciously polite battle between two stars, Carstensen and Schygulla, to the incredible camera moves and blocking within an undisguised theatrical set-up (5 acts, one set). Carstensen is fantastic, and puts the lie to Petra’s own claim that everyone is replaceable, even if the mannequins in her studio mimic the actress’s postures. The only man in the film is a tiny little penis on the awesome Poussin reproduction that covers one wall.

People are apparently replaceable in Fassbinder’s largely autobiographical Beware of a Holy Whore (1970). Events from the troubled shoot of Whity (1970), stuck in a hothouse hotel in Spain, are built into a group portrait where few of the protagonists play themselves (and many are fired), but the cruelty is real.  For example, the consistently-denigrated Irm Hermann is played onscreen by Magdalena Montezuma, who is slapped repeatedly and breaks down in public, crying that the director had pimped her out, promised to marry her, have children with her, before being banished back to Germany. The lines were taken from life, and Fassbinder had Hermann dub her own character’s voice. His own part is taken by pretty Lou Castel with a permanent scowl, but what a devastating film it would have been if Fassbinder had played himself. The whore is the cinema, without which they are all at a loose end, generally miserable, having sex and getting upset about it. The brief excerpt we see from what they are meant to be shooting ends in one of the few moments of genuine cheerfulness in all Fassbinder’s films. This is what they – and he – live for.

For example, the consistently-denigrated Irm Hermann is played onscreen by Magdalena Montezuma, who is slapped repeatedly and breaks down in public, crying that the director had pimped her out, promised to marry her, have children with her, before being banished back to Germany. The lines were taken from life, and Fassbinder had Hermann dub her own character’s voice. His own part is taken by pretty Lou Castel with a permanent scowl, but what a devastating film it would have been if Fassbinder had played himself. The whore is the cinema, without which they are all at a loose end, generally miserable, having sex and getting upset about it. The brief excerpt we see from what they are meant to be shooting ends in one of the few moments of genuine cheerfulness in all Fassbinder’s films. This is what they – and he – live for.

Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1975) may be one off Fassbinder’s most famous and popular films for the simple reason that it too is unusual in his work in presenting a love story in which we can believe, and allowing it the possibility of living on past the end of the film. There is a strong ambiguity about the mutual attraction between the old charlady and the younger, Moroccan guestworker at the start – unexpected, indiscriminate lust? Mere loneliness? – but the scene of the pair’s going to bed for the first time is one of the most touching Fassbinder ever filmed, and for a moment, it seems, he almost believes in love.

Brigitta Mira is so good in that film that Fassbinder had to use her again, and wrote for her another straight ahead, scathing criticism film that got him in plenty of trouble, Mother Küster’s Goes to Heaven (1975). She pinballs between reporters, communists, and anarchists, for the sake of preserving her dead husband’s memory after he kills an overseer and himself in the workplace. Left and right appropriate his death to mean what they want, and both sides in real life felt they were being mocked. They were. A very strange thing about this film is that it has two totally separate endings which play remarkably well together, but which imply two really quite different films. In the first, a freeze on Mother Küsters’ face is backdrop to script lines describing a confrontation between the anarchists and the police, in which, of course, she is killed. In the second, the anarchist gang is shown to be ridiculous, and Mother Küsters, is reduced to looking to a bland, if charming, nightwatchman for comfort.  The first ending makes a tract of her journey; the second makes it a more personal and touching film, her search for company in the name of her husband’s memory, with whomever will offer to listen to her, a tragic grief mechanism repeated over and over again.

The first ending makes a tract of her journey; the second makes it a more personal and touching film, her search for company in the name of her husband’s memory, with whomever will offer to listen to her, a tragic grief mechanism repeated over and over again.

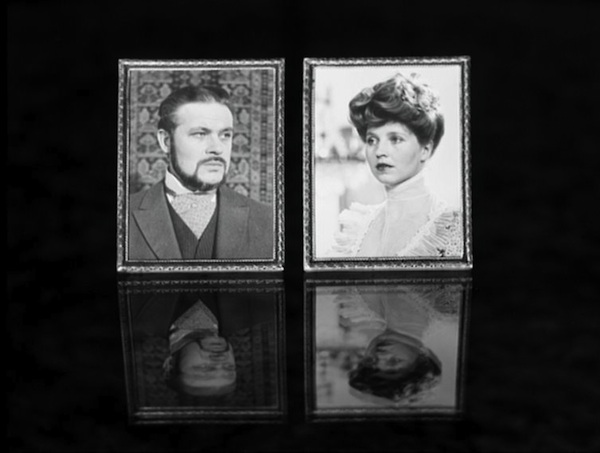

The first part of the series closed on Sunday with Fontane Effi Briest (1973-4). This is a trying film for non-German speakers, since Fassbinder’s aim was not so much to adapt the story of Fontane’s novel, but to adapt the novel itself. Albeit there is plenty of text in the film, via letters, telegrams and intertitles, there’s a great deal of dialogue and (Fassbinder’s) voiceover, much of it deliberately delivered to sound like quotation; thus the experience of reading, translated into listening, is rather undermined if one then has to read (copious) subtitles. It’s not helped by the fact that several details are dealt with skimpily or elided (the mysterious Chinaman is even more mysterious in the film; you must pay close attention to realize that the late-appearing, never-seen Rollo is a dog). More than ever, however, the story is told with camera moves and framing (and so many mirrors!), and it is fundamental Fassbinder: more time and care was lavished on the production than any other, save that other urtext, Berlin Alexanderplatz (1979), for much of Fassbinder’s personal philosophy on society and emotions was drawn directly from Fontane.  The result is remarkably successful in what it set out so oddly to do, as well as being one of his most gorgeous and compositionally rich films.

The result is remarkably successful in what it set out so oddly to do, as well as being one of his most gorgeous and compositionally rich films.

A couple of days’ rest, and then we can dive back in: Wednesday 6 starts with another autobiographical film, this time the farcical Satan’s Brew, playing at the Aero with a great Carstensen performance in Fear of Fear (a cruel, semi-comic version of Woman Under the Influence). Fassbinder’s Straubian debut, Love is Colder than Death plays on Thursday at the Egyptian, along with his gangster deconstruction/Berlin Alexanderplatz dry run The American Soldier; on Friday, his first, highly successful, melodrama film, The Merchant of the Four Seasons, shows with Gods of the Plague, almost a remake of his debut; and then the BRD trilogy is filled out on Saturday night by the visual and textual feasts of Lola and Veronika Voss. Another few days’ breathing space, and then a final chance to see the magnificent Ali again, on Thursday 14th, paired with another rather maligned title Chinese Roulette, considered by some to be pointlessly cruel and needlessly intricate in its manipulation of eye-lines and blocking, but for both those reasons and more (Carstensen and Kurt Raab), quite hilarious.