The classical film noir period may only have stretched from the early 1940s to the late 1950s, but the tone, themes, and style of film noir continue to inspire a host of modern films, or neo-noirs. One of the most stylistically successful neo-noirs of the past decade is Rian Johnson’s Brick (2005).

Unlike contemporary neo-noirs such as Chinatown (1974) or L.A. Confidential (1997), which lovingly recreate the 1930s-1950s, Brick applies the style and even the dialogue of classic film noir to a modern-day high school setting. A modern high school is a self-contained world teeming with moral strife and a perfect stand-in for the seedy underground of the classical noir city. This melding of noir and adolescence intuitively recognizes the pervasive sense of gravity shared by both and makes Johnson’s effort unique among neo-noirs.

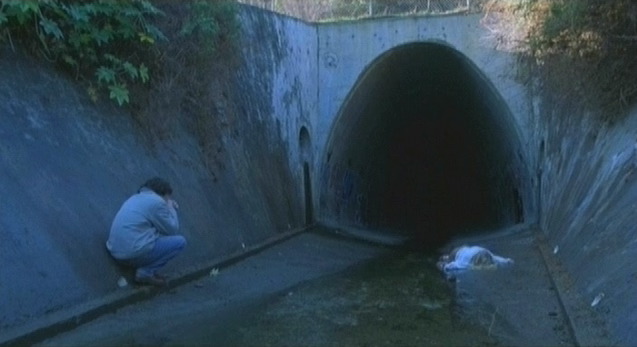

The story is just as convoluted as any classic noir, with Brendan Frye (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) as a high school loner out to solve the mystery surrounding the death of his ex-girlfriend, Emily (Emilie de Ravin). Brendan is essentially a recluse, friendless and prone to a perpetually severe expression. He realizes something is truly rotten in his high school when he finds Emily’s dead body face down at the entrance to a tunnel, having vanished after calling Brendan in a panic.

Intent on solving the mystery of Emily’s death, he enlists the help of The Brain (Matt O’Leary) in order to retrace her steps. His investigation leads him to drama student Kara (Meagan Good), the wealthy and well-connected Laura (Nora Zehetner), a violent gang member nicknamed Tug (Noah Fleiss), and his boss, elusive drug lord The Pin (Lukas Haas). Each one is a clue to Emily’s disappearance, but even Brendan is unsure who is helping him find the truth and who is leading him deep into the heart of a dangerous drug ring.

Neo-Noir Brick and Film Noir The Maltese Falcon

The influence of Dashiell Hammett and film noirs like The Maltese Falcon (1941) is unmistakable in Johnson’s writing and directing. What prevents the characters, especially Brendan, from being mere copies of classic film noir characters is Johnson’s thorough understanding of the genre. Film noir is a genre built on archetypes: the hardened detective, the femme fatale, and the corrupt criminals. In transporting these archetypes into the modern day, Johnson creates a (true), technically sound film noir, albeit one starring high schoolers.

The determined Brendan is the teenage manifestation of Hammett’s Sam Spade and Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe, equally tough and tenacious detectives. His relationship with Laura is undeniably modeled on that of Spade and Brigid O’Shaughnessy in The Maltese Falcon, going so far as to incorporate dialogue from the film. Johnson populates his screenplay with other traditional noir archetypes, as well. The myriad of characters that Brendan turns to for answers range from a modern femme fatale (Laura) to the wiry, teenage version of a Sydney Greenstreet-esque kingpin (The Pin), complete with a black falcon sculpture.

That said, Brendan is more than a cursory homage to the classic noir private eyes. He embodies the noir hero archetype. Brendan is certainly just as resourceful and witty as Spade, spitting cocky lines like, “I got five good senses and I slept last night.” He is isolated and alone, constantly at odds with others, especially authority figures. This manifests itself in the film in Brendan’s confrontations with Vice Principal Trueman (Richard Roundtree). Like any good noir hero, Brendan has deep character flaws and questionable ethics.

Johnson’s tarnished hero is plagued by his past actions, the implied reason for his break-up with Emily. In flashbacks, the film shows that Brendan tried to prevent Emily from involving herself in any underground crime and so framed their mutual friend, Jerr, for drug dealing, which led Emily to end the relationship. In this mystery thriller, what may hinder one’s suspension of disbelief the most is that this hard-boiled and jaded protagonist is, in fact, a teenager. Johnson gives no justification for this, nor does his character truly exhibit many teenage characteristics. However, the characters in Brick can be said to behave as much like teenagers as high schoolers in any teen film.

An Orson Welles Approach to Cinematography

Despite his low budget, Johnson succeeds in creating a wonderfully dark tone throughout the film by employing an Orson Welles-like approach to cinematography. A host of intriguing camera angles and revealing framing choices bolster the teenage murder mystery. Symbolically, Brendan spends most of the film trapped in the margins of the camera frame. Johnson and Director of Photography Steve Yedlin make exhaustive use of wide-angle shots to enhance the sense of isolation in this California high school.

This vast emptiness engulfs Brendan whenever he is on screen. He is truly alone, in his school’s social scene and in his search for the truth. Interestingly, these shots serve to visually convey Brendan’s isolation but simultaneously separate the audience from the action. This violent mystery is therefore very removed from any familiar reality. When he is not on the outskirts of the frame, Brendan is caught in suffocating close-ups. This perfectly captures his sheer confusion and fear when confronted with Tug and The Pin. Danger builds exponentially as the film goes on, and Johnson relates this through abrupt cuts and fades to black.

An immersive throwback to film noir, Brick is Johnson’s attempt at something new. In choosing a high school as the setting and frustrated teenagers as the protagonists, he proves that noir can transcend the crime-ridden streets of 1940s California. Brick is in every way a high concept film, but it succeeds because of Johnson’s screenplay, which combines the familiar components of classic noir with an enthralling story. The result is a world unique to this film, a pastiche comprised of old noir elements yet entirely new in their reimagined backdrop.