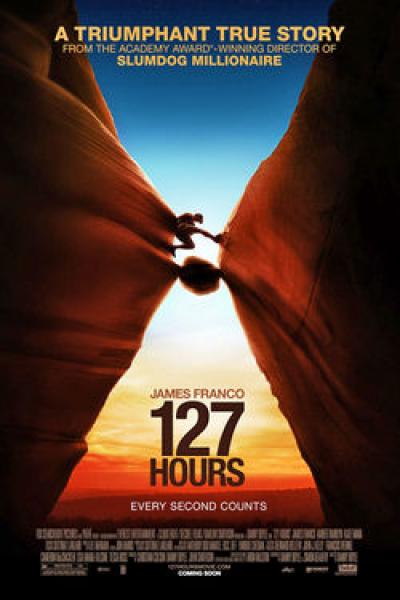

If you were alive and news-conscious during 2003, you know the story of Aron Ralston, a young mountaineer and adventure-seeker who fell through a crevasse while hiking Utah’s Blue John Canyon and wound up stuck with a boulder crushing his right arm. You also know how he got out. Ralston wrote a book about his experience “Between a Rock and a Hard Place”, and that book is now a film, its darkly ironic title replaced with a factual one, 127 Hours, the length of time Ralston was trapped. Directed by Danny Boyle with the same trademark visual flair that ignited Slumdog Millionaire to worldwide box office and Oscar acclaim, 127 Hours is likely to garner similar accolades for its visual wizardry and breathless interpretation of Ralston’s stunning true story.

If you were alive and news-conscious during 2003, you know the story of Aron Ralston, a young mountaineer and adventure-seeker who fell through a crevasse while hiking Utah’s Blue John Canyon and wound up stuck with a boulder crushing his right arm. You also know how he got out. Ralston wrote a book about his experience “Between a Rock and a Hard Place”, and that book is now a film, its darkly ironic title replaced with a factual one, 127 Hours, the length of time Ralston was trapped. Directed by Danny Boyle with the same trademark visual flair that ignited Slumdog Millionaire to worldwide box office and Oscar acclaim, 127 Hours is likely to garner similar accolades for its visual wizardry and breathless interpretation of Ralston’s stunning true story.

For those familiar with the story beats—man climbs mountain, man becomes trapped, man saws own arm off to escape—the first third of Boyle’s film grips the viewer with a built-in sense of nervous anxiety and anticipation of what lies ahead. Shot on the location at the same canyons the real Ralston climbed, the majesty of Aron’s beautiful surroundings is twinged with a dark and ironic dread. Part of this dread is alleviated when Aron (James Franco) meets up with two attractive hikers, Megan and Kristi (played by Amber Tamblyn and Kate Mara) and together the trio explodes the landscape’s natural wonders and natural highs. These young people are clearly thrill-seekers. Boyle conveys their reckless abandon with a blaring rock soundtrack, zooming camera movements and vivid color palette. These tricks are recycled with a generous helping of dramatic irony when Aron is alone, having neglected to tell the girls where he’d be. Two sequences stand out—when “Lovely Day” by Bill Withers blares over a montage of Ralston trying to lick the chalkstone boulder off his arm and when Aron’s extreme thirst triggers hallucinations of a rapid-fire rush of beverage commercials, a cheeky literalization of the Coca-Cola catchphrase “The pause that refreshes”—both recalling the time Aron spent swimming in an underground pool with the two women.

Boyle’s camera reaches everywhere, mapping out the specific geography of Ralston’s predicament. Although most of the film takes place in the tightest of confined spaces, Boyle and cinematographers Enrique Chediak and Anthony Dod Mantle eek out every angle and vantage point with a series of shifting camera lenses. Assessing his situation, Aron lays out his supplies: a water bottle, half full; ropes and carabineers; a backpack with a built-in pouch for water and straw; a cheap stocking-stuffer pocket knife; an MP3 player, out of batteries; and a camcorder, with which he’ll document his final will and testament. Ralston’s claustrophobic situation simultaneously draws the viewer in and repels, exacerbating all physical discomforts: that slight itch on your thigh, the hint of a sneeze, the tensing of an arm from the seat next to you. Have to use the restroom? Make sure you go before the movie starts.

Aron slips, falls, down, down down, the small boulder following. It lands on his arm. He’s trapped. His first words are defiant: “This isn’t fate.” And yet the film treats Ralston’s story as one with a delineated and admirable moral. Ralston must learn something from his 127 hours and the moral is the one of the oldest cliches: carpe diem. Give thanks for your family. Don’t take life for granted. A.R. Rahman’s score, punctuated by the angelic strains of Dido, practically lifts Ralston to Heaven on a cloud. If it isn’t fate, Boyle certainly doesn’t shy away from Christian, “born again” metaphors.

But Ralston is saving the inevitable until it becomes an absolute necessity. Not until he runs out of water does he finally stab himself in the arm, a gesture born out of frustrated exhaustion more than careful pre-planning. Boyle clearly delights in shocking his audience–even one that’s been waiting for the moment the entire movie–giving us a shot from inside Ralston’s arm of the blade touching up against bone. That may be the defining image of the film: one that speaks to Boyle’s no-holds barred intimacy and intensity but doesn’t actually give us anything we weren’t expecting–a clever angle on a predetermined outcome.

Because 127 Hours provokes a deeply personal reaction in viewers (look no further than the spat of faintings that have occurred during screenings), I feel I must address the film from a personal standpoint. When we finally get to the scene, it is both what you would expect and something for which I could not have possibly prepared. Boyle and editor Jon Harris construct a dizzying montage of the present and the past (Aron conjures happier memories of time spent with his girlfriend to prepare him) that is at once shocking, terrifying, gruesome and, as embodied by James Franco’s performance, triumphant. The filmmakers bend over backwards to elicit emotional reactions during the sequence, although Ralston’s recollections of a failed relationship with a heretofore-unseen girlfriend never gripped me. Instead, it is the physically visceral power I found most convincing. This scene–and indeed, the final twenty minutes of the movie–is so emotionally overwhelming, my palms are sweating just recalling it.

But herein lies my primary problem with 127 Hours: it’s an experience, not a movie. The final sequence of Ralston rejoining the world, we’re meant to believe after coming to a realization of the goodness of humanity, is totally overshadowed by the lingering effects of shock and still-pumping adrenaline in the viewer. Danny Boyle tried to convey Ralston overcoming a lifelong loneliness and aversion to people (again, the girlfriend flashback is our primary indicator, and very nearly our only avert reference to Ralston’s anti-social tendencies), but this never really comes across in the film. Franco-as-Ralston is too hip, too charming and entirely too self-aware to ever take seriously as a person who’d retreat from mankind, let alone come to a last minute Paul on the road to Damascus-type conversion.

Aron Ralston’s story is singularly unique but Boyle’s approach never seems to convey its sincerity. All the flash, which in and of itself is spectacular, yields an emptiness at the end of the film. What is the use of the split screen shots of multitude of people–marathoners, soccer crowds, the great throngs of faceless humanity Ralston is rejoining–if I don’t buy his epiphany and contrition? The net result of Boyle’s kitchen sink approach to visual style is a nervy, exhausted filmgoer hopped up on ocular adrenaline. When I got home from the screening, I immediately hugged every member of my family, more out of shock than anything. The feeling after leaving 127 Hours is comparable to that after a car crash: happy you survived but punch-drunk from the ride. With a few days’ distance, I’ve chilled towards it. The film stakes too much of its power on a faux-redemptive moral and with retrospect, isn’t nearly as engaging as it is when you’re pinned by its emotional throes.

The FilmFracture breakdown:

Production: 2 clocks

Acting: 3 clocks

Cinematography: 4 clocks

Editing: 4 clocks